Trevor Ball

For more than a decade, Mexican drug cartels have used commercially available (COTS; commercial off-the-shelf), small unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs; also called ‘drones’) to smuggle drugs across the U.S.–Mexico border and to conduct intelligence, surveillance, target acquisition, and reconnaissance (ISTAR) tasks. Increasingly, cartels are also using small UAVs to employ lethal munitions, mirroring tactics adopted in recent years by state and non-state actors across the globe. A variety of non-state armed groups—including the so-called Islamic State, Hezbollah, and Hamas—have experimented with UAV-delivered munitions since as early as 2012. This trend has continued apace:

“Increasingly, both state and non-state actors have used COTS small UAVs to execute direct strike missions using improvised air-delivered munitions (IADMs) and modified conventional munitions. Analysis of the use of these improvised and craft-produced aerial munitions in recent years has shown that, in conjunction with COTS or ‘hobbyist grade’ UAVs, they can provide a modest precision strike capability to belligerents.” — Friese, Jenzen-Jones & Smallwood, 2017.

Mexican drug cartels have used UAVs to deliver explosive munitions since at least 2017. In 2023, there were 260 documented attacks in which UAVs were used in this way. UAV-delivered munitions have been used by cartels to target both rival organisations and Mexican government personnel. An undisclosed number of Mexican soldiers have been killed by cartel UAV attacks, with at least 8 soldiers killed by IEDs of unspecified employment between 2018 and 2024. 42 people were wounded by cartel bombing attacks in 2023 by August, up from 16 wounded in 2022. UAV-delivered munitions in Mexico—whether dropped by UAVs or integrated into UAVs to form crude guided munitions—are usually reported generically as ‘improvised explosive devices’ (IEDs), which can sometimes make them difficult to distinguish from more conventional IEDs when reviewing some sources. 2,186 IEDs have been recovered by Mexican government forces between December 2018 and August 2023, with more than half of these recovered in the Mexican state of Michoacán. 2,889 UAV-delivered munitions of various designs were seized in an operation by Mexican authorities in Concordia, Sinaloa on 24 April 2025.

These organisations are clearly learning lessons about the usage of UAVs and the development and production of UAV-delivered munitions from the experiences of state and non-state actors across the globe. Mexican drug cartels’ usage of UAV-delivered munitions is not as sophisticated as that seen displayed by both sides in the Ukraine–Russian War, for example, which has increasingly been driven by the considerable power of state-backed production, but Mexican drug cartels have nonetheless developed limited craft-production capabilities. For example, munitions recovered in 2023 and 2024 are generally more sophisticated than those seen in earlier seizures. The standardisation of these devices indicates more streamlined production processes and the adoption of craft-production standards.

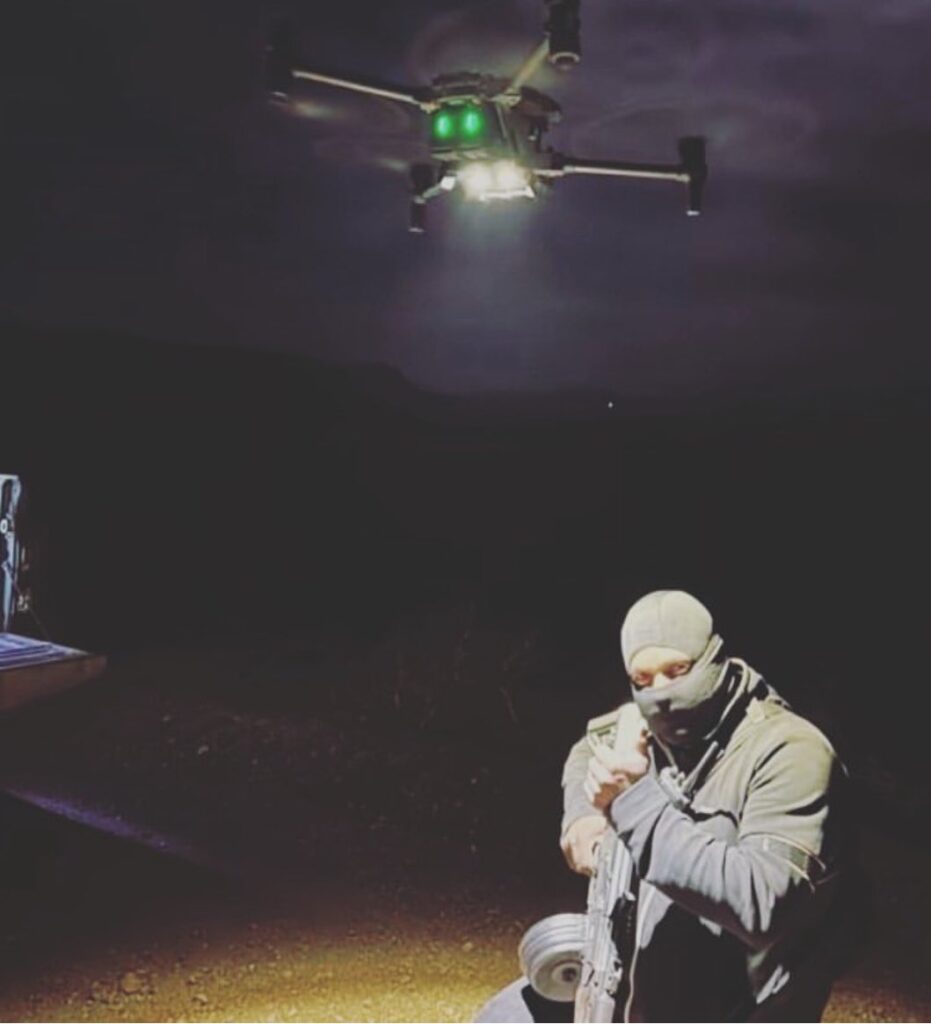

Modification of COTS small UAVs has become a fixture of modern conflict in recent years, even as states work to develop purpose-built platforms for the same roles. In line with this trend, Mexican drug cartels are using modified commercial UAVs such as the DJI Mavic and Matrice models to deliver small munitions. These models are widely available and can be easily adapted to deliver munitions (see Figure 2). Small UAVs are also used extensively in the ISTAR role, especially for the reconnaissance of rival organisations and government personnel. This includes surveillance across the Mexico–United States border, along which approximately 1,000 UAV incursions from Mexico are occurring each month. COTS small UAVs have been used to monitor government personnel on the border, and in some instances, to deliver drugs across the border. A cartel UAV observing a U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) vehicle in the United States can be seen in Video 1. A CBP officer shines a laser at the UAV, as a cheap and relatively ineffective method of countering the ISR capabilities of the platform. A wider range of counter unmanned aerial systems (C-UAS) options are being made available to CBP and Border Patrol at present. Mexican drug cartels are also employing C-UAS devices to counter UAVs operated by both rival organisations and the Mexican government (Figure 3). The procurement of these devices is more difficult and costly than acquiring COTS small UAVs, and clearly demonstrates an understanding of the importance of ‘drone warfare’ in the modern era.

The variety of small, UAV-delivered munitions used can broadly be divided into two groups: ‘air-delivered’ or ‘one-way attack’. In almost all cases when used by Mexican drug cartels, COTS small UAVs have been adapted to drop improvised air-delivered munitions (IADMs). These drones can also drop modified conventional munitions (see Figure 4, right). These types of munitions can be classified as small air-delivered bombs. While there is little evidence of use by Mexican drug cartels, modified conventional munitions or improvised explosive devices (IEDs) can be integrated into the UAV platform in such a way as to create what is essentially a crude guided missile (see Figure 4, left). The integration of a munition or IED into a UAV in such as way that the UAV is consumed with the munition results in a design often referred to as ‘one-way attack’ (OWA) UAVs. These are also sometimes referred to as ‘first-person view’ (FPV) UAVs, however this is often a misnomer based on the predominant use of FPV UAVs due to their greater speed and control compared to other UAVs.

Conventional munitions will generally need to be modified to function as intended when delivered by a UAV. The nature and extent of these modifications will vary based upon how the munition is delivered. If integrated or semi-permanently fixed to a UAV, for example, a munition’s safety, arming, and/or fuzing mechanisms may need to be modified to ensure it will detonate upon impact at a (relatively) low velocity. If a conventional munition is modified to serve as a small air-delivered bomb, it may benefit from the addition of craft-produced components, such as fins or stabilisers. Munitions normally fitted with time-delay fuzes, such as hand grenades, are sometimes modified to accept impact fuzes. If not correctly modified, UAV-delivered munitions may function prematurely, partially, or not at all.

The fight against the so-called Islamic State in Iraq and Syria, and more recently the Ukraine–Russian War, has seen the state-backed production of munitions specifically designed for UAV delivery. Nonetheless, modified conventional munitions and IADMs are still the most prevalent types globally. Mexican drug cartels have continued to develop more sophisticated munitions over the past few years, continuing to advance their designs from simple IEDs (see Figure 5) towards the craft production of munitions specifically designed for UAV delivery.

Mexican officials first arrested men with a UAV fixed with an IED in 2017. However, in April 2020, two UAVs were captured by a community defence organisation, with attached improvised explosive devices. These devices were crude, and each consisted of a plastic container filled with explosive, reportedly C4, and ball bearings that was taped to a UAV and electrically initiated. IEDs, or munitions, seized since are often clearly intended for use by UAV, featuring fins to help stabilize and orient the munition, and impact fuzing. Munitions recovered in 2023 and 2024 regularly feature fragmentation to enhance the effectiveness of the munitions, with added fragmentation liners, or the device casing being scored. These munitions overwhelmingly appear to feature crude mechanical impact fuzing, where they detonate on impact with the ground or another surface. Numerous videos from cartels show UAVs capable of carrying and dropping several different munitions in a single sortie—a significant upgrade over the devices first pictured in 2020 (see Video 2).

According to Mexico’s Defense Secretary, Luis Cresencio Sandoval, most explosive devices recovered in Mexico make use of black powder as the explosive charge, or use explosives stolen from the commercial mining industry. There are few publicly available images that show the explosive filler, or internal components, for these munitions. Figure 6 shows a UAV-delivered munition that appears to be filled with a commercial ammonium nitrate/fuel oil (ANFO) mix. The filler material is consistent in shape, grain size, and colour with commercial ANFO (e.g. small pellets or ‘prills’ of a pinkish colour). ANFO is often used incommercial mining operations, and the presence of ANFO in these munitions would be consistent with Secretary Sandoval’s statement. These specific munitions appear to be filled with approximately 0.6 lbs (~270 g) of ANFO, which in equivalent in explosive power to about 0.5lbs (~230 g) of TNT. This is broadly comparable to the explosive power of an M67 hand grenade, used by Mexican and American armed forces, (0.53 lbs TNT equivalent). Mexican drug cartels’ chemistry (drug manufacturing) capabilities and access to chemical precursors means that there is a significant risk of these organisations producing their own, more powerful explosives rather than relying on the theft or purchase of commercial mining explosives for UAV-delivered munitions.

Currently, there are no open-source indications that cartels have developed an anti-armour capability for their UAV-delivered munitions. Such designs are commonplace elsewhere, and typically feature a shaped charge. Mexican drug cartels possess armoured vehicles, which makes the future development of anti-armour or dual-purpose UAV-delivered munitions very likely as conflicts between rival organisations continue to escalate. New variants and further developments of UAV-delivered munitions continue to appear frequently. In March 2025, a munition believed to be the largest UAV-delivered munition thus far seen in use by Mexican cartels was captured by Mexican officials (see Figure 7). This munition is estimated to have roughly three times the explosive capacity of the UAV-delivered munitions seen in Figure 6.

FPV UAVs, typically used as OWA or ‘sacrificial’ UAVs, are prevalent in the Ukraine–Russia war, but only one possible FPV OWA UAV has been recorded in Mexico. Figure 8 shows a DJI Avata 2 model UAV, that was possibly intended for use as an OWA munition. The red box denotes possible bulk explosive material, while the green circle denotes a possible indicator that the initiation device failed to properly detonate the bulk explosives. If this figure does indeed show explosive material, it would represent the first public imagery of an OWA UAV being used in Mexico.

Munition Examples

The following figures show a variety of munitions designed to be employed by UAVs that have been seized by Mexican authorities, or posted on social media by cartel members, between March 2021 and April 2025. This is not an exhaustive list of UAV munitions recorded by ARES during this time period, and UAV munitions are regularly used, and seized, in Mexico. Some organisations, or units within organisations, are clearly more sophisticated than others. Figures 14, 15, and 16 all show munitions seized in Sonora, Mexico, that have a mostly standardised, uniform construction. While constructed from widely available pipe material, they have been scored to enhance fragmentation, feature impact fuzing, and have been fitted with stabilising fins. Other examples examples of UAV-delivered munitions recovered in Mexico show considerably less sophistication, with some being extremely crude. Often munitions will have different sized fins, for example. One example below uses part of a plastic bottle for a stabiliser.

Special Thanks to Twitter/X Users: All Source News (@All_Source_News) and Pernicious Propaganda (@natsecboogie) for their extensive documentation of Mexican drug cartel activities.

Sources

Associated Press (AP). 2023. ‘Mexican army says drug cartels are increasing their use of roadside bombs’. 22 August. <https://apnews.com/article/mexico-1581883d951c8f7a79ac5c61ec558b78>.

Associated Press (AP). 2024. ‘Mexican Army Acknowledges Some of Its Soldiers Have Been Killed by Cartel Bomb-Dropping Drones’. 2 August. <https://apnews.com/article/mexico-drug-cartel-drone-attacks-soldiers-killed-572b39c73c030bef20257517d1c4a91d>.

Axe, David. 2017. ‘Great, Mexican Drug Cartels Now Have Weaponized Drones’. VICE News. 25 October. <https://www.vice.com/en/article/mexican-drug-cartels-have-weaponized-drones/>.

CBS News. 2023. ‘Drug cartels are sharply increasing use of bomb-dropping drones, Mexican army says’. 23 August. <https://www.cbsnews.com/news/drug-cartels-more-bomb-dropping-drones-mexico-army/>.

CBS News. 2023. ‘Raid uncovers workshop for drone-carried bombs in Mexico house built to look like a castle’. 4 October. <https://www.cbsnews.com/news/mexico-jalisco-police-raid-drone-bombs-house-castle-drug-cartels/?ftag=CNM-00-10aab7c&linkId=239368163>.

CBS News. 2024. ‘Explosion kills 2 Mexican soldiers in suspected booby trap by drug cartel after troops found dismembered bodies’. 18 December. <https://www.cbsnews.com/news/explosion-kills-soldiers-booby-trap-drug-cartel-mexico/>.

‘El Huaso’ & ‘Enojon’. 2023. ‘Los Viagras Use Drone Bombs Against CJNG in La Ruana, Michoacán’ Borderland Beat. 15 September. < https://www.borderlandbeat.com/2023/09/la-ruana-michoacan-is-hotspot-of-drone.html>.

Friese, Larry. 2017. ‘Islamic State unmanned aerial vehicle shot down in Iraq’. The Hoplite. 1 December <https://armamentresearch.com/islamic-state-unmanned-aerial-vehicle-shot-down-in-iraq/>.

Friese, Larry Friese, N.R. Jenzen-Jones & Michael Smallwood. 2017. Emerging Unmanned Threats: The Use of Commercially Available UAVs by Armed Non-state Actors. Perth: Armament Research Services.

Fulmer, Kenton & N.R. Jenzen-Jones. 2017. ‘Improvised Air-delivered Munitions in Syria & Iraq: A Brief Overview. C-IED Report. Spring/Summer 2017.

Gonzalez, Juan Manuel. 2020. ‘Con drones, CJNG busca erradicar a rivales en Tierra Caliente’. La Silla Rota. 12 August. <https://lasillarota.com/estados/2020/8/12/con-drones-cjng-busca-erradicar-rivales-en-tierra-caliente-242161.html>.

Hamilton, Keegan & Kate Linthicum. 2024. ‘Soldiers and civilians are dying as Mexican cartels embrace a terrifying new weapon: Land Mines’. Los Angeles Times. 9 March. <https://www.latimes.com/world-nation/story/2024-03-09/mexico-cartel-land-mines-weapons>.

Jenzen-Jones, N.R. 2020. ‘Understanding the Threat Posed by COTS Small UAVs Armed with CBR Payloads’ in M. Martellini & R. Trapp (eds.), 21st Century Prometheus: Managing CBRN Safety and Security Affected by Cutting-Edge Technologies. Cham: Springer Nature.

Lucio, Charbell. ‘Dos elementos de la GN lesionados, tras enfrentamiento con CJNG en Chinicuila’. Revolucion News. 25 May. <https://revolucion.news/dos-elementos-la-gn-lesionados-tras-enfrentamiento-cjng-chinicuila>.

Mx Politico Editorial Team. 2024. ‘Decomisan arsenal bélico y 52 artefactos explosivos para lanzar con drones en Michoacán’. MX Politico <https://mxpolitico.net/decomisan-arsenal-belico-y-52-artefactos-explosivos-para-lanzar-con-drones-en-michoacan/>.

Noroeste. 2024. ‘Aseguran explosivos, armas y detienen a dos personas en operativos en Sinaloa’. 24 April. <https://www.noroeste.com.mx/seguridad/aseguran-explosivos-armas-y-detienen-a-dos-personas-en-operativos-en-sinaloa-BL12082443>.

Olay, Matthew. 2024. ‘NORAD Commander: Incursions by Unmanned Aircraft Systems on Southern Border Likely Exceed 1,000 a Month’. Department of Defense. <https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/3707785/norad-commander-incursions-by-unmanned-aircraft-systems-on-southern-border-like/>.

Sánchez, Ramón. 2024. ‘Muere policía de Tamaulipas tras ser atacado con dron explosivo’. Posta. 17 October. <https://tamaulipas.posta.com.mx/mexico/muere-policia-de-tamaulipas-tras-ser-atacado-con-dron-explosivo/vl1624184>.

Resendiz, Julia. 2024. ‘Cartels drop bombs from drones, set vehicles on fire in Michoacan’. Border Report. 28 August. <https://www.borderreport.com/regions/mexico/cartels-drop-bombs-from-drones-set-vehicles-on-fire-in-michoacan/>.

Stalinsky, Steven and R. Sosnow. 2017. A Decade of Jihadi Organizations’ Use of Drones: From Early Experiments by Hizbullah, Hamas, and Al-Qaeda to Emerging National Security Crisis for the West as ISIS Launches First Attack Drones. Washington, D.C.: MEMRI.

Trevithick, Joseph. 2020. ‘Drug Cartel Now Assassinates its Enemies with Bomb-Toting Drones.’ The Warzone. 27 November. <https://www.twz.com/36013/mexican-drug-cartel-now-assassinating-its-enemies-with-improvised-explosive-toting-drones>.

Warrick, Joby. 2017. ‘Use of weaponized drones by ISIS spurs terrorism fears.’ The New York Times. 21 February. <https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/use-of-weaponized-drones-by-isis-spurs-terrorism-fears/2017/02/21/9d83d51e-f382-11e6-8d72-263470bf0401_story.html>.

Wright, Galen & N.R. Jenzen-Jones. 2018. ‘Improvised, Craft-produced and Repurposed Munitions Deployed from UAVs in Recent Years’. C-IED Report. Spring/Summer 2018.

Remember, all arms and munitions are dangerous. Treat all firearms as if they are loaded, and all munitions as if they are live, until you have personally confirmed otherwise. If you do not have specialist knowledge, never assume that arms or munitions are safe to handle until they have been inspected by a subject matter specialist. You should not approach, handle, move, operate, or modify arms and munitions unless explicitly trained to do so. If you encounter any unexploded ordnance (UXO) or explosive remnants of war (ERW), always remember the ‘ARMS’ acronym:

AVOID the area

RECORD all relevant information

MARK the area from a safe distance to warn others

SEEK assistance from the relevant authorities