This post accompanies the eighteenth in a series of collaborative videos produced with ARES Researcher Ian McCollum, who also runs the Forgotten Weapons blog and YouTube channel. Using access to unique collections facilitated by ARES, this series of videos will examine a range of interesting weapons over the coming months. Each video will be accompanied by a blog post, here on The Hoplite, and supported by high quality reference photographs. – Ed.

Jonathan Ferguson

The De Lisle Carbine manually-operated rifle was the brainchild of William Godfray de Lisle, and was manufactured from 1943 by the well-known Sterling Arms Company. It is one of a number of near-legendary suppressed firearms that actually begin to approach the stereotypical Hollywood silencer sound effect in terms of actual report. It achieves this effect by addressing all three of the major aspects of firearms sound generation: the mechanical noise of the action; the sound generated by the sudden release of high pressure gases following the projectile; and, in some cases, the supersonic ‘crack’ of the bullet as it breaks the sound barrier. The rear half of the weapon is a Short Magazine Lee-Enfield rifle converted to fire .45 ACP pistol cartridges, providing a manually-operated mechanism that would not reciprocate and make noise. The .45 ACP cartridge is inherently subsonic, solving another challenge of suppressing firearm. The .303 magazine was replaced with a Colt 1911 pistol magazine, modified to fit the SMLE magazine catch. With a truly detachable magazine, the charger bridge was removed.

This arrangement addressed two out of the three factors. Taking care of the ‘uncorking’ of propellant gasses was achieved by the total replacement of the front half of the gun. This now comprised two major assemblies. Firstly, a very short (7″ or 175 mm) barrel was ported to bleed off propellant gases and the muzzle was counter-bored into a flared internal profile. Both measures encouraged rapid reduction of gas pressure at the muzzle, greatly reducing report. Over this was fitted an integral suppressor of substantial length (longer than the barrel) and diameter, providing a large internal volume in which propellant gases expand and cool. The internal arrangement of the suppressor consists of the usual Maxim-style convoluted metal disc baffles. Open tangent style sights were installed on the suppressor tube, graduated from 50 to 200 yards. The front sight is very simple, with a U-shaped sheet metal protector. Some examples, including the production example shown in the video, were also fitted with small dampening pads under the bolt handle to eliminate the ‘clack’ of the bolt stem contacting the metal of the action body.

The majority of De Lisle Carbines (500) were intended to be produced with their original fixed SMLE butt-stocks. However, 50 were earmarked for a folding ‘para’ stock. The sole surviving example of a folding stock De Lisle Carbine resides today at the Small Arms School Corps collection at Warminster, UK. The stock itself is of the same design as the Patchett Machine Carbine, which was in parallel development at Sterling at the time. As with the Patchett/Sterling, the stock is extremely solid when deployed, but is not quick into action, requiring multiple steps to unfold and lock into place. However, in actual use there would be no need to keep the weapon folded if action was expected. As a strictly offensive weapon, the user is likely to know when he needs his stock.

Effectiveness

The end result of this effort was one of the quietest suppressed firearms ever developed. Suppressor technology may have improved since, but the overall De Lisle Carbine package remains close to the zenith of quiet operation in a shoulder arm (although this may be largely due to a lack of a stated requirement). The closest modern-day equivalent in a service weapon is probably seen in the integrally suppressed Ruger 10/22 rifles used by Israeli forces; of course, these weapons fire a much smaller projectile and are not used in the De Lisle’s intended role.

Eighteen prototype De Lisle Carbines were produced at Dagenham for testing, of which six were dispatched to Belgium; at least one survives there today. Period tests (reproduced in Rome’s article) yielded 85.5 db. This was compared to a Sten sub-machine gun, suppressed (89.5 db) and unsuppressed (125 db). As with period figures for the Welrod, these are remarkably low by modern standards and cannot be compared with modern numbers for other weapons. Nonetheless, they do demonstrate the relative effectiveness of this legendary weapon.

Testing of a Valkyrie Arms reproduction was also reported in Rome’s article and produced 119 db, which compared to 155 dB for an unsuppressed 10” barrel Marlin Camp Carbine. This really is very quiet, and despite the lack of a truly faithful De Lisle reproduction, compares well with the period data. The author too has fired a modern reproduction, which subjectively possessed a report similar to a sub-12 ft/lbs air rifle. Paulson, who also tried the Valkyrie repro described it as being quieter than a “Crosman pellet pistol”. This is supported by a period memo titled ‘Observations on the De Lisle carbine and its probable use in Malaya’, dated 4 December 1950 (UK National Archives reference WO 291/1651):

‘During a talk given in the open to a number of visiting officers at the FARELF Training Centre, a De Lisle carbine fired 5 rounds within fifty yards of the audience without any member of the audience realising that a rifle had been fired.’

This is the tactical context that must be borne in mind when weapons such as the De Lisle are claimed to be ‘silenced’ or ‘silent’. This means only that an observer (i.e. the enemy) at 50 yards would not recognise the report as that of a rifle (or even a firearm). However, one period report (from a Major Mack, see below) actually did report that there was ‘no bang whatsoever’. This hardly seems possible, but does in any case speak to the legendary reputation of the type, and the scarcity of suppressed firearms at the time. Any suppressed firearm was impressive at the time – the De Lisle doubly so. Hence, we also encounter the almost certainly apocryphal story of informal testing against London’s pigeons which, whilst perfectly plausible given the weapon’s capabilities (and the noise of London’s streets even in the 1940s), is not supported by written sources. In reality, the infamous silent pigeon slaughter ‘meme’ very likely originated with stories of actual urban testing. As Ian Skennerton relates, De Lisle himself reported that ‘imperceptible’ shots were made at a Piccadilly chimney in the course of testing early prototypes. It is tempting to imagine that the prototype example now in the Royal Armouries collection, with its distinctive slim tube marked ‘The De Lisle Commando Carbine’, might have been the very ‘chimney’ prototype in question, but of course there is no evidence for this.

In terms of reliability, limited use in the field makes it difficult to pass judgement. However, SMLE heritage and a suitably stout suppressor body would have made the weapon relatively robust. The only real identified issue is a rather anaemic ejector which requires positive operation of the bolt to throw an empty case properly clear of the action. An endurance trial by the Armaments Design Dept, Small Arms, Cheshunt on July 15 1944 reported that the weapon “suffered badly from coking” but only after several thousand rounds. The suppressed Sten and ‘Welsilencer’ Sten apparently did better, although it could be argued that this is because the De Lisle was doing its job of capturing propellant gases better than the competition!

British General Gerald Templer test firing a De Lisle carbine, Perak, Malaya, 1952 (source: British National Army Museum Identification Code NAM 1981-04-77-1).

Usage

The De Lisle was designed for use by special operations forces, primarily the British Commando Brigades, rather than for dropping to partisans as in the case of the Welrod. However, SOE operatives did receive examples (see below) and the test and evaluation reports in the former Pattern Room archive make clear that the weapon was recommended by SOE as a sentry removal weapon for ‘bandit camps’ in far east. Successful testing resulted in an order of 550 being placed, with 500 of those to be fitted with a fixed wooden stock, and 50 with a folding metal stock. However, as Ian notes in the video, the British military outlook had changed by the time that sufficient numbers of the De Lisle were available in 1943. The contract was cancelled, by which time only 130 or so had been made, including the sole folding stock example. A patent was applied for in May 1943, and granted in July 1946.

In 1957, the De Lisle was resurrected for service in Malaya. Strangely, some of these (Paulson claims 100 examples, but does not provide evidence) were supplied to British ex-pat planters, seemingly as personal/property defence weapons. These farmers frequently encountered local terrorists on their land, and the De Lisle offered a discreet way to combat them. It presumably acted as a deterrent in that terrorists could not know when (or from where) they were being engaged. Rome’s article (p.32) lists several instances of recorded usage, mostly post-Second World War. However, Mike Burke, former Jedburgh leader claimed “…two hits against field-grade Nazi officers early in 1944” using a De Lisle left behind by an SOE operative. Allen Knorrs claimed one was to be smuggled into Europe for assassination of “top level German officers and officials”. Rome quotes journalist Geoff Heath:

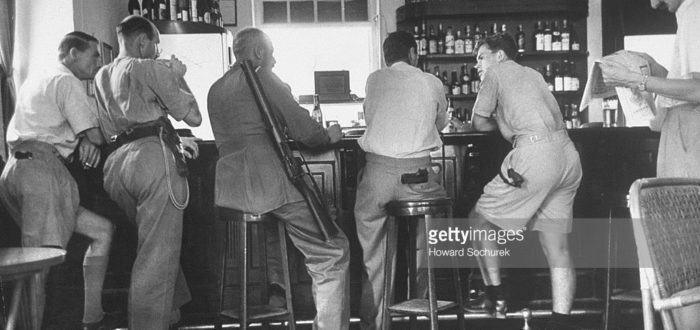

“It was not uncommon to venture into a club in Kuala Lumpur and see our chaps with silenced Stens and the De Lisle here and there.”… “Anywhere beyond your own fence and lights was terrorist country after dark. Our chaps used to stake out in those areas, like their old special mission days in the last war, and try to kill the terrorists with the silenced weapons – beat them at their own game of terror. Some of our people were SOE, you know, and had used the De Lisle before.”

Also from Rome we hear of former OSS Captain Mitchell L. WerBell’s activities in Burma, who would go on to become a famous designer of suppressors in his own right and invented the Vietnam-era ‘Destroyer’ suppressed carbine:

“We worked a couple against sentries before raids and they were something else…better than the stuff we were issued. Both our people and the British used them in Indochina…Merrill’s boys used them to terrorize and scare the shit out of the Japs at night and in ambush.”

Ian Skennerton also reports an instance from Burma:

“An instance of such use, reported by a sniper, was when the carbine was used for picking off Japanese troops in open lorries behind the Japanese lines. The British snipers were laid up near the road, well camouflaged, and they silently dispatched a Japanese in each lorry that passed. In most cases the lorry would stop, but as no shot was heard, they found it hard to believe that they had been fired upon, or indeed, if they had. from whence it came. In the reported case, there were two or three such snipers operating along the road, and they bagged three or four in each lorry.”

Finally, Major D. I. A. Mack, then a lieutenant platoon commander within the 1st Battalion Royal Scots Fusiliers, deployed during the Malaya Emergency in 1955:

“Kroh, 13 Feb 55 [Sunday] I and my platoon tried out a new weapon today (new to us), the Delisle [sic] silent carbine. This is a very cut-down rifle adapted to fire .45-inch and fitted with a silencer. It looks like a rifle butt and breech joined on to a long cylinder and it is meant for the silent knocking of bandit sentries or for any other occasion when one wants to run out a chap without warning his muckers of the wrath to come. It was the first time I have ever seen a silent weapon fired and it was rather uncanny as there was no bang whatsoever – just the click of the released firing pin, the whiz of the bullet (not heard normally) and the thump as the bullet hits the stop-bank (or body). In the jungle most of the noises would be smothered and would pass unnoticed if not unheard.”

This seems to be where the De Lisle story ends, pending release of any relevant classified material. Unlike the longer-lived Welrod, there are no other documented post-war uses of the type, which is likely a result of a lack of tactical imperative and the scarcity of surviving (and serviceable) examples post the 1950s.

Technical Specifications (Prototype)

Calibre: .45 ACP

Overall length: 950 mm (37.4”)

Barrel length: 175 mm (7″)

Weight (with empty magazine): 3.745 kg (8.26 lbs)

Feed device: 7-round detachable magazine

Technical Specifications (Fixed-stock Production variant)

Calibre: .45 ACP

Overall length: 905 mm (35.6”)

Barrel length: 175 mm (7″)

Weight (with empty magazine): 3.415 kg (7.53 lbs)

Feed device: 7-round detachable magazine

With thanks to Mark Murray-Flutter (Royal Armouries Museum). Header image from Getty images (LIFE magazine); ‘Rifles and pistols are slung on the shoulders and pockets of planters lining up in a bar.’ February 01, 1952| Credit: Howard Sochurek.

Special thanks to the National Firearms Centre at the Royal Armouries, who graciously allowed us access to their world-class collection for this and other videos and photos, as well as to another collection which has elected to remain confidential.

References/Further Reading

Royal Armouries online collection;

https://collections.royalarmouries.org/object/rac-object-279389.html

https://collections.royalarmouries.org/object/rac-object-275988.html

https://collections.royalarmouries.org/object/rac-object-275987.html

-Mack, D.I.A. ‘Kroh, 13 Feb 55 [Sunday]’. The Journal of The Royal Highland Fusiliers, 2006 Edition, Volume 30, p.96. http://www.rhf.org.uk/JOURNAL/2006%20Journal.pdf

-Moss, Matthew. 2016. DE LISLE SILENCED COMMANDO CARBINE. Historical Firearms. http://www.historicalfirearms.info/post/141628223744/de-lisle-silenced-commando-carbine-the-de-lisle

-Paulson, Al. 2004. ‘De Lisle .45 ACP Silent Carbine’, Special Weapons for Military & Police, pp.56-61. http://www.valkyriearms.com/images/DeLisle_article.pdf

–Rifleman.org.uk. ‘The De Lisle Carbine’. http://www.rifleman.org.uk/The_DeLisle_carbine.htm

-Rome, Robert (June 1984). ‘WWII Silent Killer Still Lives’. Gung Ho magazine, pp.26–32.

-Iannimico, Small Arms Review “The British De Lisle Commando Carbine,” by Frank Iannamico – May 2013.

-Skennerton, I. 1998. Special Service Lee-Enfields: Commando & Auto Models. Small Arms Identification Series No. 13.

Remember, all arms and munitions are dangerous. Treat all firearms as if they are loaded, and all munitions as if they are live, until you have personally confirmed otherwise. If you do not have specialist knowledge, never assume that arms or munitions are safe to handle until they have been inspected by a subject matter specialist. You should not approach, handle, move, operate, or modify arms and munitions unless explicitly trained to do so. If you encounter any unexploded ordnance (UXO) or explosive remnants of war (ERW), always remember the ‘ARMS’ acronym:

AVOID the area

RECORD all relevant information

MARK the area to warn others

SEEK assistance from the relevant authorities

7 thoughts on “British De Lisle Carbine bolt-action rifle”