We are excited to introduce the first in a series of collaborative videos produced by ARES Researcher Ian McCollum, who also runs the Forgotten Weapons blog and YouTube channel. Using access to unique collections facilitated by ARES, this series of videos will examine a range of interesting weapons over the coming months. Each video will be accompanied by a blog post, here on The Hoplite, and supported by high quality reference photos. Stay tuned! – Ed.

Ian McCollum

Great Britain was one of the few countries that went into World War Two having undertaken virtually no submachine gun (SMG) development. Not every country had issued an SMG by 1939, but almost all major military powers had been working on experimental concepts. Germany, for example, was developing a number of concept guns during the interwar period, which would eventually result in the highly regarded MP 38. Many countries had already successfully employed SMGs in the First World War, and understood their military utility. The British had only a small number of minor SMG developments in the interwar period, none of which progressed past the prototype stage. It was only with the outbreak of hostilities that the British need for such a weapon suddenly became apparent and its acquisition became a military priority.

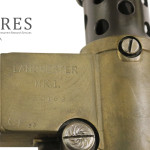

As a stopgap measure, two German MP 28/II submachine guns were acquired in Ethiopia, and a plan set in motion to more or less copy them outright. The result of this reverse-engineering process was the Lanchester. This design was an effective and high quality weapon, and provided an option besides the painfully expensive commercial purchase of Thompson guns from the United States – each Thomspon gun costing some three to five times as much as a Lanchester. During discussions with the armed services regarding each branch’s desired number of Lanchesters, the Army indicated they had no need given the acquisition of Thompson guns. Whilst the Royal Air Force expressed a limited interest, this was scaled back by the time the guns were manufactured. The Royal Navy was the primary supported of the Lanchester concept, asking for the provision of 50-round magazines with the guns, and ended up acquiring nearly all of the approximately 50,000 Lanchesters produced. In fact, Lanchester SMGs saw limited Naval use into the 1970s, chained to ship bulkheads to provide arms to repel boarding-parties. However, the Lanchester featured a lot of machined parts and a wooden butt-stock, and still proved too expensive and time consuming to produce.

In an effort to dramatically simplify the Lanchester, the Sten Mark I (Mk.I) was born. The Sten, taking its appellation from the first letters of the surnames of its designers – Major Reginald V. Shepherd and Harold Turpin – and ‘EN’ from ‘Enfield’ (the Royal Small Arms Factory Enfield), where the gun was developed. With a development period of less than six weeks, the Sten was essentially a study in removing all the non-essential elements from the Lanchester design. The Sten Mk.1 still featured wooden furniture components, and was fitted with a folding fore-grip and flash hider, and was adopted in March 1941. This design reduction was still determined to be more elaborate than necessary, however, and the Mk.I* was soon introduced. This interim development removed the fore-grip, wooden furniture, and flash hider. In total, some 300,000 Mk.I and later Mk.I* SMGs were produced. Nonetheless, further manufacturing expediency was sought; within just a few months of adoption, the Mk.I and Mk.I* were superseded by the Sten Mk.II.

The development and production timelines of the various iterations of the Sten gun were astonishingly fast, despite the weapon’s relative simplicity. By August of 1941, the Sten Mark II had entered production. The Mk.II was truly a study in spartan submachine gun design. All the wooden components were done away with. The barrel shroud was shortened to the bare minimum necessary to keep the shooter from burning their hand on the barrel. The stock was simplified to just a single strut and a flat plate. Whilst a crude and simplistic weapon, it was cheap and fast to make, requiring just 5.5 man-hours per gun and costing some 7 per cent of what a Thompson had cost. This was a weapon that would rearm Britain and be delivered to resistance movements across Europe – nearly 2.5 million of these weapons were produced between 1941 and 1945. The Sten Mark III was very similar to the Mk.II, but made with a stamped and welded tube receiver instead of a seamless tube. It was developed simply to exploit different manufacturing infrastructure, and more than 800,000 of these were made alongside the Mk.II.

Holding the Sten Mk.II and Mk.III securely has always been something of a problem. Whilst the 1942 manual instructs soldiers to hold the weapon by the handguard, there are images showing some troops opted to grip the gun by the magazine or magazine well. The design of the gun did not lend itself to ergonomics, and there remained several possibilities to burn one’s hand or introduce malfunctions to the gun by improper hand placement under combat conditions. As the war progressed and the immediate threat of a German land invasion of the British Isles faded, there was time available to made some much-appreciated improvements to the Sten. In the Mk.V guise, a good wooden butt-stock and pistol grip were added, along with a Lee Enfield front sight and bayonet lug (note that no ‘Sten Mk.IV’ was ever adopted). These guns were mechanically the same, but much more user-friendly and ergonomic. The Mk.V was manufactured from February 1944 until the end of the War, with some 527,000 being produced.

With the end of World War Two, the time came to retire the Sten and develop a better design to carry the British armed forces forward. The Sten had always embodied a conscious comprise of quality for expediency, but now that compromise was no longer necessary. In the late 1940s and very early 1950s, Britain would test a number of potential replacements.

The Vesely V-42 was designed in Britain by a Czech refugee named Josef Vesely, who applied for patents in 1942 and 1943. The V-42 was a particularly unusual creation, with a clever but complex 60-round magazine comprised of two separate 30-round columns. It failed to get beyond prototype stage, but three other weapons did: the MCEM (Machine Carbine Experimental Model) series, a family of guns made by BSA (Birmingham Small Arms), and George Patchett’s improvements to the Sten design. A number of different trials took place, with the most important in 1947, 1949, and 1951.

The MCEM guns were rather quickly dropped from testing. The example examined in the video is from the MCEM-2 series (including the later MCEM-4 and MCEM-6), a small sub-machine gun with the magazine well located in the pistol grip. The MCEM-2 series was first developed by Polish small arms designer Jerzy Podsędkowski in 1944, and trialled in 1947. It may be considered by some to be a ‘machine pistol’; whilst large, it could be fired one-handed, and is fitted with a fire selector for semi-automatic fire. When fired in automatic mode, it had an unacceptably high rate of fire of approximately 1,000 rpm (later models featured rate reducers). The detachable butt-stock is of a hollow design made of a stiffened woven fabric, and is designed to serve double duty as a holster. It also features an unusual bolt design which is charged with the finger, which was likely to cause issues.

The BSA guns were much better, and featured a creative charging system in which the front handguard of the gun was, in its entirety, a cocking handle. One would pull the handguard forward and them press it back to manually cycle the bolt. Whilst an interesting design, it was no doubt more complex than was desired. These featured a design layout similar to the earlier Sten and their competitor, the Patchett, and fired at a much more practical 600 rpm. Much like the Patchett, the BSA guns also featured under-folding wire stocks.

It was George Patchett’s gun – first prototyped all the way back in 1942 – that would prove the winner. Patchett, working at the Sterling Armaments Company in Dagenham, essentially worked to refine the Lanchester/Sten design for modern service. He designed a low profile folding stock, moved the grip assembly forward on the gun, and most importantly developed a new and much-improved magazine for his gun. Where the Sten had used a single-feed magazine prone to jamming (adopted in a rush as a copy of the MP 28/II magazine), Patchett instead employed alternating-feed (sometimes called ‘dual-feed’ or ‘double-feed’) geometry. He added rollers to the magazine follower, and gave the magazine body a slight curve. The result was one of the best submachine gun magazines designs ever produced. Magazines are a critical component for automatic firearms, and especially otherwise simple blowback-operated submachine guns, and Patchett’s design would propel his weapon to adoption in 1953 as the L2A1. It was subjected to a handful of minor improvements before entering mass production in 1955 as the L2A3. Produced by the Sterling company and becoming commonly known as the Sterling SMG, Patchett’s gun would remain in British military service until 1994.

Special thanks to Neil Grant. All images copyright Armament Research Services, unless otherwise indicated.

Gallery 1 – Lanchester

Gallery 2 – Sten Mk.I

Gallery 3 – Sten Mk.III

Gallery 4 – Sten Mk.V

Gallery 5 – V-42

Gallery 6 – MCEM

Gallery 7 – BSA

Gallery 8 – Patchett types

Remember, all arms and munitions are dangerous. Treat all firearms as if they are loaded, and all munitions as if they are live, until you have personally confirmed otherwise. If you do not have specialist knowledge, never assume that arms or munitions are safe to handle until they have been inspected by a subject matter specialist. You should not approach, handle, move, operate, or modify arms and munitions unless explicitly trained to do so. If you encounter any unexploded ordnance (UXO) or explosive remnants of war (ERW), always remember the ‘ARMS’ acronym:

AVOID the area

RECORD all relevant information

MARK the area to warn others

SEEK assistance from the relevant authorities

Pingback: British Submachine Gun Overview: Lanchester, Sten, Sterling, and More! – Surplused