Jonathan Ferguson

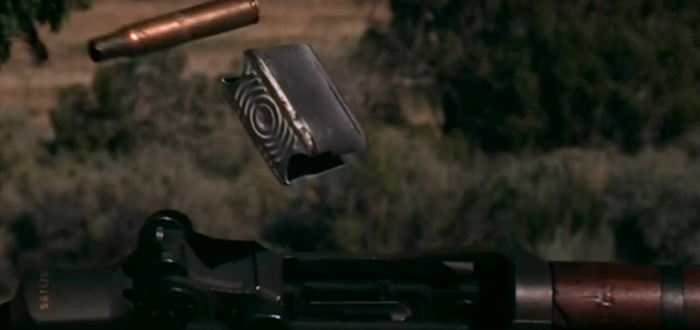

One of the most persistent firearm myths is that American soldiers fighting in the Second World War (or later, in the Korean War) were at substantial risk of being identified and engaged by the enemy because of the distinctive ‘ping’ sound made by ejection of clips from their issued rifles. The M1 ‘Garand’ was ahead of its time as a military self-loading rifle, but unlike modern rifles it did not feature detachable box magazines. Instead it was loaded with eight round metal en bloc clips. These were inserted into the open action from the top and retained inside the weapon until the last round was fired, at which point the clip would eject (along with the final fired cartridge case) with a distinctive ‘ping’ sound (you can clearly hear this in the movie ‘Saving Private Ryan’, for example, and see it in slow motion in this Forgotten Weapons video). The notion of this ‘ping’ being a fatal flaw is a myth, in that there’s no evidence that it endangered infantrymen. However, there’s a bit more to it than that…

A lot of ink and pixels have been expended arguing the ‘M1 ping’ myth back and forth, and some have even tried to practically demonstrate why it’s a silly idea. Tactical trainer Larry Vickers recreated a scenario for his ‘TAC TV’ series, and more recently YouTuber ‘Bloke on the Range’ has tackled the myth. The Bloke shows just how difficult it would be to even hear the ‘ping’, without the various other loud noises associated with battle. Soldiers have only recently begun to wear any kind of hearing protection at all, which would have made such a noise even more difficult to detect. Not to mention the obvious fact that soldiers rarely fight alone. Even if a German or Japanese soldier did manage to take advantage of the ‘ping’ window of opportunity, he’s likely to get shot by another GI. More importantly, the Bloke shows how easy and quickly one could reload following the ‘ping’. At all but the closest ranges, this really is a myth and a total non-issue. As Bloke points out, there is no actual historical evidence for this ever having happened, and for every claim that a veteran experienced it, there is an ‘equal and opposite veteran’ making a claim to the contrary. This is typified by an exchange in ‘American Rifleman’ magazine in 2011/12 (reproduced here). It’s almost impossible to find a first-hand account either; it’s always a relative, a friend, or a friend-of-a-friend, and being told and retold decades after the fact. At this point, one would normally call ‘case closed’ as Garand expert Bruce N. Canfield has done online, in no uncertain terms.

However, this situation is more complicated than just the bare facts. Sometimes, myths intrude into reality by being thoroughly embedded in thought and practice. There is no doubt whatever that whether this ever happened or not, quite a lot of soldiers in the ‘40s and ‘50s clearly did believe that this quirk of their rifle posed a real threat. This is proven by a fascinating document uploaded by the Garand Collector’s Association. 1952 Technical Memorandum (ORO-T-18 (FEC)), entitled ‘Use of Infantry Weapons and Equipment in Korea’, was written by G.N. Donovan of ‘Project Doughboy’. This was an effort by the Operations Research Office of the John Hopkins University to gather feedback on the practical usage of US military weapons in the then-current Korean War.

On page five we read the conclusion that:

“The noise caused by ejection of the empty clip from the M1, despite the fact that at close range it could be heard by the enemy, was considered valuable by the rifleman as a signal to reload.”

And on page eighteen:

“One other complaint about the M1 was the noise made by the safety. Half the men had a nagging fear that some day the noise made in releasing the safety would reveal their positions to the enemy, yet only one-fourth objected to the distinctive noise the empty clip made when ejected. They were quite willing to retain the noise of the clip even though the enemy might be able to use it to advantage, because they found it a very useful signal to reload.”

However, the question that prompted this response was rather a leading one (p. 51):

“Interviews Conducted on Noise of the Rifle

- Is the sound of the clip being ejected of possible help to the enemy or is it helpful to you as an indication of when to reload, or is it of no importance?

[Answers are followed by the number of men responding in the affirmative]

Helpful to the enemy – 85

Helpful to know when to reload, therefore retain – 187

Of no importance – 43

[Total responders – ] 315”

But the answers speak for themselves. Of those soldiers surveyed, twice as many believed that the noise was helpful to the enemy, as thought it unimportant. Many more men thought it was actually a useful audible indication of an empty weapon, bearing out the Bloke’s results that yes, you can hear the ping if you’re close enough, but no, you probably can’t successfully rush a man before he can get another clip into his rifle.

In defence of their findings, the researchers commented thusly:

“Results of these interviews show that there is great uniformity in responses to questions asked, and all numerical estimates of such items as range of firing, load carried, etcetera, have been found to cluster around a central point with comparatively little scattering. Thus it is felt that the results are reliable and can be fairly said to represent what the infantryman believed he did. The fact that these were group interviews further increased the reliability of the results, since any apparent exaggeration by one man was quickly picked up and questioned by others. In this way the men themselves provided a check on the accuracy of their answers.”

In other words, if other soldiers thought it impossible for the enemy to take advantage of the ‘ping’, they would have said so. This is probably true, although interviewees are likely to behave differently under observation and questioning, and so some doubt must remain. There was also no recommendation made with respect to this perceived ‘flaw’ with the weapon, and no comment from officers on the issue (interestingly, they did point out that the noisy safety could be carefully operated not to make noise). However, again, the numbers here speak for themselves, along with the later anecdotal evidence. Some soldiers really did believe that it was possible for the enemy to hear the ‘ping’ of your rifle, rush your position, and kill you. And, whilst unlikely, there’s no reason to believe that such a thing is impossible. For example, in an incident that occurred in Afghanistan in 2008, a skirmish between a British patrol and a small number of Taliban came down to just such a one-on-one situation, with a British officer and Taliban fighter positioned just feet from each other with only a river bank in the way. Realising his weapon was empty, the attacking officer opted to use his bayonet (and the element of surprise) rather than take time to reload, and killed the wounded enemy.

If we imagine a similar engagement where one party is armed with a Garand, it may well be possible to hear the final shot and the clip go ‘ping’, close the distance, and kill the unfortunate combatant. There are many other scenarios in which this could happen, but all would involve a lull in firing, being isolated from one’s squadmates (or at least in their firing line, preventing them from shooting past you), running out of ammunition at just the wrong moment, and a certain amount of bravery and/or luck on the part of the defender. It may have happened, it may never have happened; on that question the balance of the evidence suggests that it did not. However, and this is an important caveat, it is important not to insist that this claim is a total myth as Canfield has done, stating that it is ‘…so silly as to not be worthy of serious discussion’. The implication is that no-one with any knowledge of the subject would make this claim, but we now know that many veteran combatants who fought with this rifle, in fact, believe it. They simply believed that the minor risk posed by the noise was outweighed by the benefit of an audible cue to reload the weapon.

Remember, all arms and munitions are dangerous. Treat all firearms as if they are loaded, and all munitions as if they are live, until you have personally confirmed otherwise. If you do not have specialist knowledge, never assume that arms or munitions are safe to handle until they have been inspected by a subject matter specialist. You should not approach, handle, move, operate, or modify arms and munitions unless explicitly trained to do so. If you encounter any unexploded ordnance (UXO) or explosive remnants of war (ERW), always remember the ‘ARMS’ acronym:

AVOID the area

RECORD all relevant information

MARK the area from a safe distance to warn others

SEEK assistance from the relevant authorities

Pingback: These Brits debunk the deadly M1 Garand ‘ping’ myth | We Are The Mighty

Pingback: Signs & Feedback: the Basics – GD Keys